Art and culture in Murcia

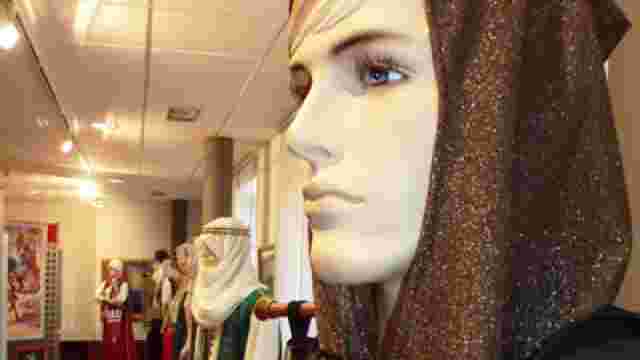

HOLY WEEK

Anyone attending a procession in Murcia for the first time, specially one of the most popular processions, will witness a series of astounding images that…

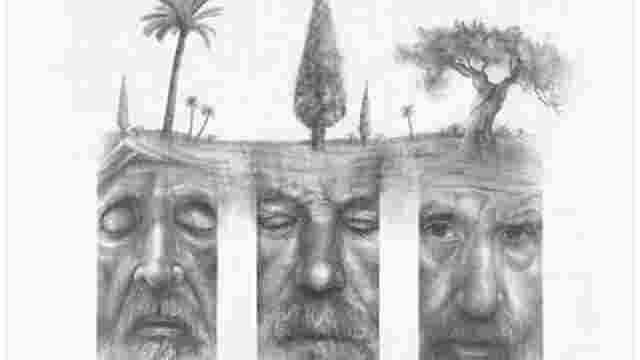

Anyone attending a procession in Murcia for the first time, specially one of the most popular processions, will witness a series of astounding images that have no equal in Spain. A celebration such as the Holy Week only gains personality and difference through the years, and Murcia counts on some Brotherhoods from the Middle Ages: the beginning of the 15th Century, when the plague and famine devastated a population left at random, that turned to faith in order to look for a remedy. In the year 1400, a river of blood started up. That blood dyed the dresses the same red that fiercely covered the body of Christ with pain. Time after that -centuries after that-, with the ups and downs of history, the Brotherhoods multiplied until they reached the splendour and vitality they are so proud of today.

We are talking about 15 Brotherhoods: fifteen associations, each one with thousands of moved processionists that turn into estantes, penitents or musicians responsible for the sound that accompanies and characterises certain parts of the processions -the long sound of the tubas, instruments that are as huge as the groans they produce.

Let's talk about some more figures. During the days of the processions, starting with the Viernes de Dolores -Dolores Friday-, more than 80 groups go through Murcian streets. It is a true open-air religious art exhibition that summarizes almost five centuries of the Murcian imagery's development. Important artist names are Francisco Salzillo, whose mention brings to mind the Baroque, skill, tact, depth and moving beauty, and also Roque López, Domingo Beltrán and Nicolás de Bussy, all of them great sculptors, honourably followed on the essentials by the artists of the present century.

People coming to this city for the first time will be able to verify that Murcian generosity is not just literature but also a real thing, and that it is even present at its processions. The processions have turned something that used to be a necessity into a very peculiar characteristic: people brought some food from the huerta -irrigated areas used for cultivation-, where they lived, to the city, to be prepared for the procession's long route. That is why today, from the swollen bellies of the Nazarenos, all kinds of presents come out. These presents can be fresh broad beans or sweets, pastries or hard-boiled eggs; it is a celebration full of generosity, maybe difficult to understand at first. Despite this, that generosity has much to do with the spirit of these days, when the greatest generosity ever is commemorated: the generosity of offering the own life to the others.

We are talking about 15 Brotherhoods: fifteen associations, each one with thousands of moved processionists that turn into estantes, penitents or musicians responsible for the sound that accompanies and characterises certain parts of the processions -the long sound of the tubas, instruments that are as huge as the groans they produce.

Let's talk about some more figures. During the days of the processions, starting with the Viernes de Dolores -Dolores Friday-, more than 80 groups go through Murcian streets. It is a true open-air religious art exhibition that summarizes almost five centuries of the Murcian imagery's development. Important artist names are Francisco Salzillo, whose mention brings to mind the Baroque, skill, tact, depth and moving beauty, and also Roque López, Domingo Beltrán and Nicolás de Bussy, all of them great sculptors, honourably followed on the essentials by the artists of the present century.

People coming to this city for the first time will be able to verify that Murcian generosity is not just literature but also a real thing, and that it is even present at its processions. The processions have turned something that used to be a necessity into a very peculiar characteristic: people brought some food from the huerta -irrigated areas used for cultivation-, where they lived, to the city, to be prepared for the procession's long route. That is why today, from the swollen bellies of the Nazarenos, all kinds of presents come out. These presents can be fresh broad beans or sweets, pastries or hard-boiled eggs; it is a celebration full of generosity, maybe difficult to understand at first. Despite this, that generosity has much to do with the spirit of these days, when the greatest generosity ever is commemorated: the generosity of offering the own life to the others.

PLAZA DE ABASTOS DE VERÓNICAS MURCIA

MURCIA - TOURIST OFFICE

Tourist Info Office Murcia Cardenal Belluga Square Telephones: 968 35 86 00. Ext. 50681/50682/50683

SALZILLO MUSEUM

Salzillo Museum. It was opened in 1960 and deeply remodelled in 2002 by the architect Yago Bonet Correa. It is a mixture of typologies: we have the Baroque…

RAMÓN GAYA MUSEUM

Ramón Gaya Museum. It is located in a beautiful mansion of Murcian style of the 19th century, the "casa Palarea" (Palarea house), and it shows the work of…

MUSEO DE SANTA CLARA

Santa Clara Museum. On the Islamic-Mudejar palace of the Emir of Murcia, Ibn Hud, the monastery of Santa Clara was founded, which since 1365 houses the…

MUSEO DE MOROS Y CRISTIANOS DE MURCIA

Las fiestas más populares de la ciudad de Murcia son las de Moros y Cristianos, de ahí que la comisión de fiestas se decidiera a crear un museo…

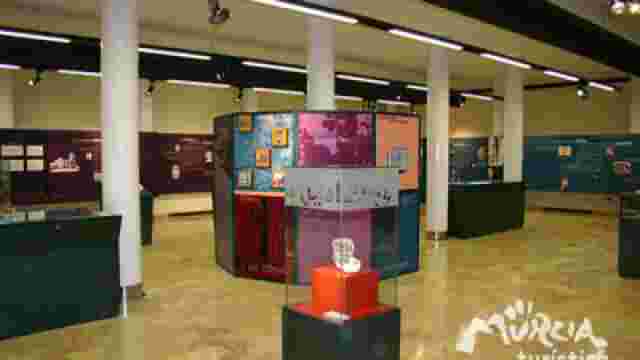

MUSEO DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE MURCIA

Museum of the University.

MUSEUM OF THE CITY

Museum of the City is located in the old house of the nineteenth century of the Lopez-Ferrer family, and on the same site where the Tower of Junterón,…

MUSEUM OF SCIENCE AND WATER

Museum of Science and Water.

MUSEUM OF THE CATHEDRAL OF MURCIA

Museum of the Cathedral.

MUSEO DE LA ARCHICOFRADÍA DE LA SANGRE

Museum of "La Sangre".

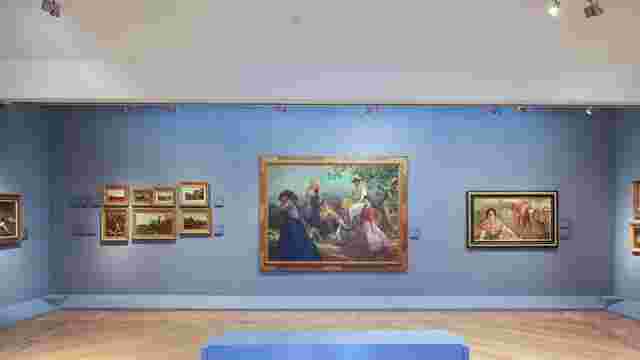

FINE ARTS MUSEUM

The Museum of Bellas Artes (Fine Arts) of Murcia is one of the most established institutions of our Region. Its origin is linked to the Comisión Provincial…

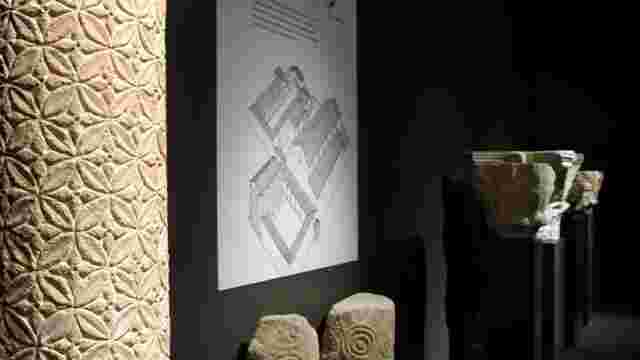

ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM

The Archaeological Museum is located in the House of Culture. At the beginning it was built as Provincial Palace of Archives, Libraries and Museums, thanks…

ESPACIO MOLINOS DEL RÍO / SALA CABALLERIZAS

Hydraulic Museum "Molinos del Río”.

CONJUNTO MONUMENTAL SAN JUAN DE DIOS

There are three essential thematic areas in the San Juan de Dios Monumental Complex: the church, the area dedicated to the sculptor González Moreno in the…

CASA-MUSEO DEL BELÉN

No hay que irse muy lejos para disfrutar del Belén de Puente Tocinos. Su casa-museo se ubica en la Casa Torre del pueblo, más conocida como la del Reloj.…

TEATRO CIRCO DE MURCIA

Los teatros-circo adquieren relevancia en París y de ahí se extendieron a multitud de ciudades europeas, una de ellas fue Murcia. Éste en concreto lo…

SANTUARIO NTRA. SRA. DE LA FUENSANTA

Fuensanta´s Sanctuary

REAL CASINO DE MURCIA

Real Casino de Murcia. Antiguamente los casinos culturales eran utilizados principalmente por personas de alto estatus social. Éste data del año 1847…

PALACIO EPISCOPAL

Su construcción comenzó sobre el año 1754 y la riqueza patrimonial que tiene hay que agradecérsela al maestro Baltasar Canesto, que fue quien dispuso…

PALACIO DEL ALMUDÍ

Almudí Palace.

CATEDRAL DE MURCIA Y MUSEO DE LA CATEDRAL

The most important temple in the Region is a magnificent merge of styles, a catalogue of stone which summarizes more than six centuries of art and history.…

CASA DÍAZ-CASSOU

Definitely, the Díaz Cassou's House is the most important and characteristic building of Modernist style in the city of Murcia. It was commissioned by…

PLAZA CARDENAL BELLUGA

Plaza concebida como espacio en el siglo XVIII, lugar de encuentro de visitantes y ciudadanos, testigo de espectáculos y festivales con el incomparable…

AC HOTEL MURCIA

A modern, urban and comfortable hotel strategically located in the city of Murcia. AC HOTELS designs a new style to feel the city offering a high quality,…

HOLY WEEK

Anyone attending a procession in Murcia for the first time, specially one of the most popular processions, will witness a series of astounding images that…

MOORS AND CHRISTIANS FESTIVITIES

Moors and christians camps and popular parades of their troops and musical groups provide festivities with a historic colour and the finishing touch is the…

ENTIERRO DE LA SARDINA

The Entierro de la Sardina (Burial of the Sardine) is the end of the Fiestas de Primavera (Spring Festivities) which are held in Murcia. In this way, the…

INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION OF TUNAS COSTA CÁLIDA

This Festival has been celebrated since 1988. During it, tunas from different countries such as Colombia, Holland, Puerto Rico and, of course, Spain. There…

CARNIVAL IN CABEZO DE TORRES

For three day, Cabezo de Torres becomes one of the centres of attraction of the Region. There are four parades and a costume competition which are…

BANDO DE LA HUERTA

This is the most important day of the Fiestas de Primavera (Spring Festivities) of the city of Murcia. The celebration starts early in the morning with an…

WARM UP ESTRELLA DE LEVANTE

FESTIVAL MURCIA TRES CULTURAS

FESTIVAL INTERNACIONAL DEL FOLKLORE EN EL MEDITERRÁNEO

ANIMAL SOUND

CENTRO DE VISITANTES MURALLA DE SANTA EULALIA

Visitors Centre of The Wall of Murcia.

CENTRO DE VISITANTES DE MONTEAGUDO (SAN CAYETANO)

Visitors Centre of Monteagudo.

TEATRO ROMEA

Con más de 150 años de historia, el ecléctico edificio del Teatro Romea es uno de los referentes culturales más importantes de la ciudad. Construido…

LEMON POP

ART NUEVE

LA AURORA

La Aurora. Galería de arte contemporáneo.

T20

T20. Galeria de arte contemporáneo.

CARAVACA: RELIGIÓN Y FIESTA